The way we design and interact with industrial products today cannot be sustained.

The stats paint a dire picture:

This is an emergency and we must completely rethink how we design artefacts and the built environment.

One key challenge is that even beyond the rapid evolution of technology, many products become victims of perceived obsolescence: losing their appeal or functionality not because of technological limitations, but because they are no longer 'trendy' or able to match consumer preferences.

Quintessential experiences have led to similar functional specialisations in our brains and common perceptual, cognitive and behavioural responses.

These experiences therefore provide stimuli which can influence people in predictable ways, even across different cultures.

Stimuli like these — 'biophorms' — could be used as design patterns for the near-universal design of interactions, behaviours and experiences.

Furthermore, we might be able to use biophorms' 'supernormal', hyperfunctional qualities to make our designs more resistant to boredom and change.

Through dialogue with artists, designers, psychologists and neuroscientists, this experimental and highly exploratory research project outlined a tentative manifesto for the application of biophorms to reduce the redundancy and waste of 'trendy' mass produced products, helping us connect to and become closer to our (shared) nature.

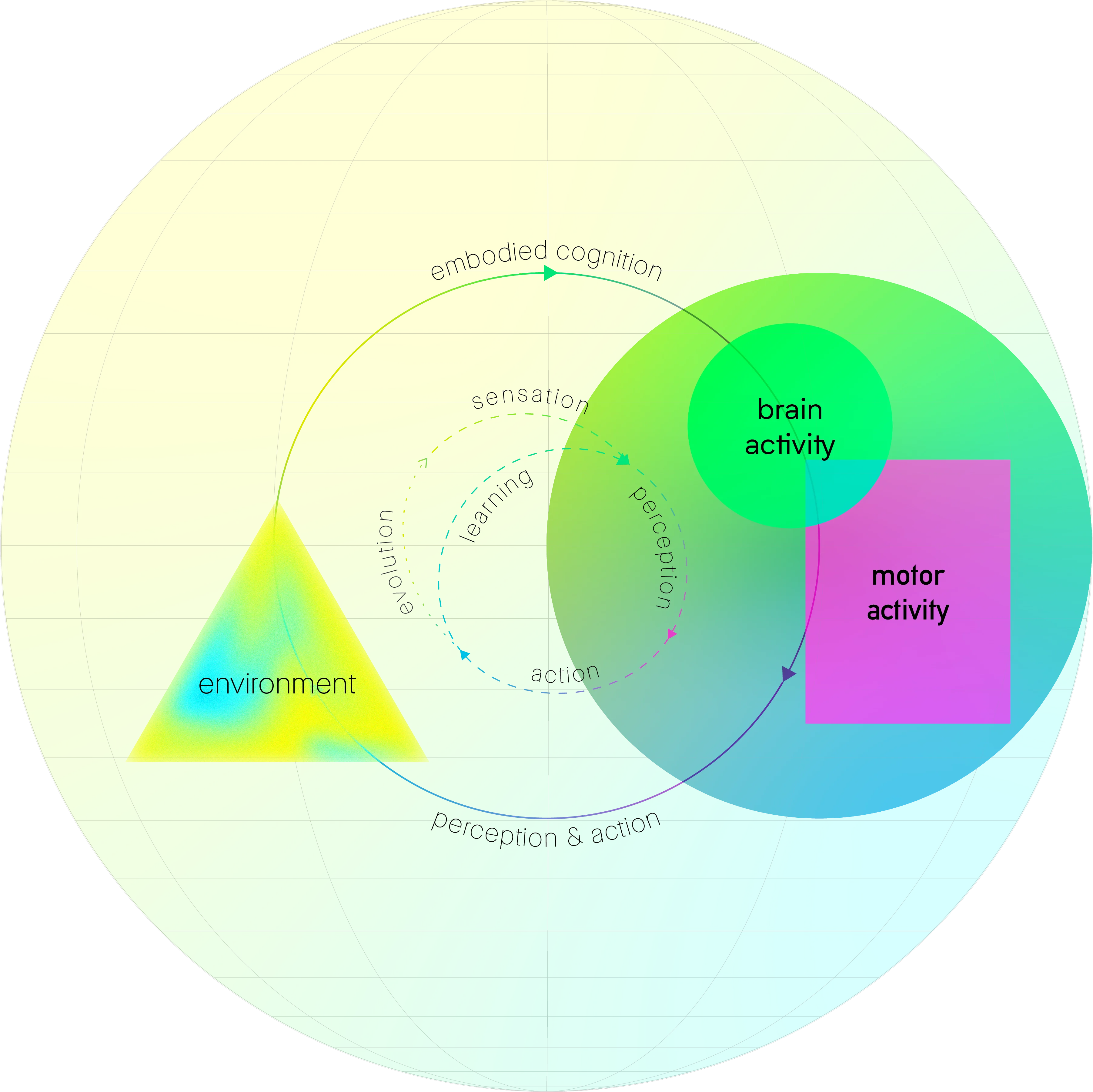

Synthesises 3 prominent theories to model the feedback

loop between our sensory-perceptual architecture and

behaviour.

This model proposes that perception and behaviour is

dependent on the expectations and therefore goals and

intentions of a person within their context of use.

This integrative view of our interactions with the

environment highlights the interplay of:

Neuroscientific research has uncovered that certain areas of the visual cortex are specifically attuned to certain categories of stimuli that have key ecological significance.

Though it is important to recognise that our brains are highly complex and interconnected, the basic structure and function of these areas are remarkably similar across the human population.

This suggests they are to a certain extent genetically hardwired and spontaneously organise across individuals through our common interactions with the environment.

‘Gnostic Fields’

Proposed specialised domains of the inferotemporal cortex (adapted from Konorski, 1967; after Livingstone, 2020).

Common experiences that are particularly significant over our evolutionary and social lives seems to have led to highly-specialised areas of the brain — and these are generalisable across humans (see Zeki & Chén, 2019; Bignardi, Ishizu & Zeki, 2020).

Some responses are clearly socially ingrained (e.g. to text), whilst others could possibly be evolved and inherited (e.g. to faces or gestures).

More of these specialised responses are likely to be revealed with time. For example, recent evidence has discovered regions of the visual cortex with high selectivity for food (Jain et al., 2023).

As social beings, we are dependent on other humans for survival. This is especially true during our early development; where we cannot survive without social care.

This seems to have not only led to a brain area which is

specialised for faces (the FFA1), but also to highly attuned responses.

We have developed highly attuned expectations about what faces look like.

When we view these faces the right way up, they're jarring because they disrupt those precise expectations.

However, when the faces are upside down, our expectations are less finely attuned and precise. As a result, it's harder to perceive the distorted features and they do not cause the same 'visual shock'.

Violating our highly specialised, biophormic expectations about the world (like we have for faces or body parts) seems to lead to a consistent 'visual shock' in the brain (see Zeki & Ishizu, 2013).

"Frontoparietal activation distinguishes face and space from artifact concepts"

An example set of stimuli (Chen & Zeki, 2011).

Further studies into this phenomenon (Chen & Zeki, 2011) suggest that this visual shock to violated body parts not only persists but actually increases over repeated exposure.

In contrast, distorting things which are less significant parts of everyday experience (or possibly survival) — like chairs and aeroplanes — leads to a relatively short-lived shock which diminishes with repeat exposure.

This provides tantalising, though currently equivocal, evidence for the potential to use biophorms as tools to predictably and continuously influence our feelings and behaviours.

There are examples across the animal kingdom of highly instinctual responses to different stimuli.

The Australian jewel beetle mistakes a beer bottle for a mate (BBC, n.d.).

A very common stimulus comes into focus, which—as a berry—is a significant aspect of our evolutionary past: leading to a strong psycho-behavioural response by virtue of its colour-texture combination (after Cuykendall and Hoffman, n.d.).

Sometimes these instinctive responses can be hijacked by stimuli that exaggerate those features.

The common patterns of brain activity suggest a certain predictable influence on our thoughts and feelings.

Does this extend to our behaviours? Or does individual, cultural or contextual experience make any influence redundant in terms of behavioural outcomes?

Proof-of-concept, biophorm investigation tool

Investigating interactions to visual stimuli in 3D space under conditions which allow a high degree of control as well as improved ecological-validity.

The embodied nature of experience and intertwining of

our sensory, perceptual and behavioural pathways

underpins the motivation to:

The complex interplay between (1) Evolutionary Pressures, (2) Social Conditioning and (3) Individual Differences highlights the necessity of:

This basic research probe investigates how we could better investigate the behavioural affordances of visual stimuli, under controlled conditions and using a 3D environment that allows us to approach the simulation of real-world user context.

This exploratory, theoretical and experimental interdisciplinary research project probed a novel approach to design, called 'biophormic design'. Biophorms are stimuli which afford thoughts, feelings and behaviours which are near-universal due to our common sociobiology. If they do indeed exist and can be understood, they could help us create intuitive, timeless products and environments.

This exploration raised a number of questions:

Triangulating evidence across several different disciplines, experimental perspectives and paradigms (including ethology, psychology, neuroscience and anthropology), I used interdisciplinary desk research to identify a range of putative biophorms — perceptual specialisations that seem likely to be either evolved or prototypical in their experience across cultures.

This evidence encourages a tentative hypothesis that certain stimuli are likely to stimulate consistent feelings and behaviours across users due to their highly typical experience across different social settings, and perhaps even over our common evolutionary history.

Focussing on visual perception, the desk research uncovered a range of credible psychological triggers and behavioural affordances worthy of further testing. For example, brightly coloured berry/fruit textures stimulating attention and hunger; symmetrical, attractive faces directing our attention and stimulating a sense of beauty; or sexually-suggestive advertising capturing our attention and driving desire or lust.

Through an analysis of current experimental techniques, a novel investigative technique was developed which probes the possibilities of user research using mixed reality (XR).

XR techniques provide a novel approach to user research, with a number of advantages:

Unfortunately, due to COVID-19 the planned exhibition was cancelled and I had to pivot from a VR-based experience to a desktop-based one.

I used the desktop app in remote workshops to observe participants' behavioural preferences whilst they provided ongoing commentary to describe their thought processes — intended to avoid post-rationalisation biases. This meant I was unable to record quantitative data about their interactions in 3D space as planned, but did bring reveal some interesting reaction patterns.

These patterns included a predicted preference for manipulating the ostensibly more salient features of the face as opposed to other areas of the head. There were also strong emotional responses to these different deformations; commonly humour and horror, which could correspond to highly cross-cultural affordances which are not typically at play in depictions of more realistic facial forms, and could prove useful psycho-behavioural stimuli to use in design.

It suggested this experimental technique shows promise worthy of further investigation, making me confident that it was more than just a gimmick—which I had feared by the change to the even less natural and immersive form of interaction enabled by the interface of a computer as opposed to a VR head/handset.

By blending design research with insights from evolutionary psychology, cognitive science and neurobiology, a fresh perspective is provided into the research of affordances and user interactions.

This study serves as a starting point, bringing some of the topic’s evidence and conceptual frameworks into light and providing a springboard for further conversation.

As it is today, our instincts are often being exploited and used by design patterns. For example, companies like Amazon can A/B test a huge number of webpage configurations — letting them tap into our fundamental intuitions and direct our attention. This type of research can exploit our intuitions or encoded heuristics with no understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

In the future, where we live in an even more 'mixed' reality through our wearables, the capacity to influence us and uncover those underlying mechanisms will only grow. It will be useful to understand biophorms before they are exploited without genuine understanding, working out how to regulate them and use them for good.

By delving deeper into our common sociobiology, and developing improved methods to explore participants' responses to stimuli in ecologically-valid environments, we could create a new paradigm for design that is more human-centred and possibly even 'more-than-human'-centred.

With many thanks to Semir Zeki, Chris McManus and Laura Ferrarello for their inspiration, critique and advice.